Get What You Want By Finding a Spot That’s Unoccupied

When I was nine years old, I fell in love with baseball and dreamed of playing first base. To aid me in my dream, my dad bought me a first baseman’s glove. When my friends and I gathered after school for an informal ball game, everyone knew to stay away from first. That was my spot.

Then something happened to change that.

The Little League season was starting up, and I decided to join the local team. During tryouts, the manager told us kids to run onto the field and man the position we most wanted to play. I of course sprinted towards first, but was in for a shock.

Five other kids had beaten me there. Apparently, each of us had the same dream. The manager told us that to win the job we’d have to compete with one another. Before he held the competition, though, he scanned the rest of the field.

Every position had at least one kid occupying it; that is, except for catcher. No one had claimed that spot. “Who wants to catch?” the manager asked. “We need a catcher.”

All of us froze. Catching was the sport’s most thankless position. As a catcher, even when the temperature outside hit 95 degrees, you still had to wear a helmet, chest protector, shin guards, thick metal face mask, and heavy padded glove. A hundred times a game, you needed to squat low and bolt back up. What’s more, foul balls stung you and base runners knocked you down. No one wanted to play catcher.

All of us froze. Catching was the sport’s most thankless position. As a catcher, even when the temperature outside hit 95 degrees, you still had to wear a helmet, chest protector, shin guards, thick metal face mask, and heavy padded glove. A hundred times a game, you needed to squat low and bolt back up. What’s more, foul balls stung you and base runners knocked you down. No one wanted to play catcher.

Which is why I was surprised when I found myself jogging towards home plate to pick up the catcher’s mitt laying there. “Good,” the manager said. “Levy will catch.”

What happened? Why did I suddenly toss aside my plan to play first base? It was out of dread. Although I’d never seen those five other kids play, my nine-year-old self was certain they were better than me, and I didn’t want to be embarrassed.

If the story ended there, it would be one of failure. But it doesn’t end there.

As a catcher, I learned how to block the plate, snag pop-ups, calm jittery pitchers, and in other ways be a credit to my position. At the season’s conclusion, I was selected –- as a catcher –- to represent my team in the All-Star game. I ended up playing a sport I love while excelling in my role.

What’s all this have to do with business? My becoming a catcher marks the first time I can remember using a strategy that has since become a cornerstone of my consulting work.

That strategy: To get what you want, find a spot that’s unoccupied.

Finding an unoccupied spot is at the heart of business positioning. After all, if you have unlimited money, talent, and connections, your business can go head-to-head with anyone in the world. If you don’t have copious resources, though, it’s best to pick a narrow-yet-important position in which you can dominate.

Finding an unoccupied spot doesn’t just work for positioning your company. It’s also a strategy that can help you write books, give speeches, and reach the media.

I’ll give you an example.

A month back, a friend (Thanks, Dan!) sent me a media query from a “Fast Company” magazine writer doing an article on how to be a good conversationalist. Getting quoted in that article would help my business. I knew, though, that dozens, maybe even hundreds, of experts would be answering that writer’s query. How could I stand out from among those other respondents?

I thought about positions. More precisely, I asked myself, “What are those other respondents likely to say?” (Which spots will be occupied?). Then I asked, “What can I say that’s different?” (Which spots will be unoccupied?)

When I thought about what the other respondents might say about being a good conversationalist, I came up with advice like “Be interested in the other person” and “Listen more than you speak.” It’s not that that advice is wrong. In fact, it’s great advice. It’s just that I’ve heard it before, so if I repeated it, I’d lower my chances of making it into the article.

Once I thought about what others would likely say, I came up with a few points about good conversation that were true yet more unusual. I emailed those points to the writer. You can see the resulting “Fast Company” article here.

What for you is the takeaway?

Whether you’re positioning your business, or creating content for a book, post, or speech, begin by asking yourself what the audience expects. If you only give them what they expect, they have no reason to listen to you.

Try finding a spot that’s unoccupied. One that’s valuable yet surprising.

Look At Your Business As If It Were a Book

Coming up with a persuasive marketplace differentiator for your business can be difficult.

One reason why: Since your business is your livelihood, creating its differentiator seems like a life-or-death decision. You tense up, thinking: “This differentiator of mine has got to be a one-of-a-kind, revenue-generating winner. Otherwise, I’m sunk.”

Trying to complete such an overwhelming exercise naturally shuts you down. The differentiator you come up with is weak. Or, you leave the exercise with no differentiator at all. What to do?

In the past decade and a half, I’ve created differentiators by the hundreds. One of my secrets: I play with how I see a client’s business. I look at it in different ways.

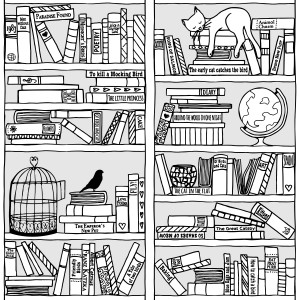

I even pretend that my client’s business isn’t a business at all. Instead, I pretend it’s a book.

Whether you realize it or not, your business is indeed a lot like a book.

Like a book, it has a main idea. It’s “about” something. That main idea may be sharp and distinct, or it may be broad and commoditized. It may be easy for people to talk about, or it may be fighting with other ideas, so talking about it is hard.

As I study a business, I think, “Right now, what’s the main idea here, and what are all the pieces of philosophy, facts, and stories substantiating that idea? If this business had a table of contents, what would the chapters be called and in what order would they fall?”

As I study a business, I think, “Right now, what’s the main idea here, and what are all the pieces of philosophy, facts, and stories substantiating that idea? If this business had a table of contents, what would the chapters be called and in what order would they fall?”

While I’m examining things, I look for storylines that are buried, or that hadn’t been thought of before. I ask myself, “If this new storyline were brought to the fore, how would that change everything? Who would be the readers for this new ‘book’? What would they be buying? How would they talk about it to friends?”

Consider trying this exercise for yourself.

Pretend your business is a book. Into which category would it fit? What would be its title? What about its main idea? Could you tweak that idea to make it stronger? Could you change the book’s meaning by moving a subordinate idea up front? Could you combine a series of subordinate ideas into something new and valuable? What would its cover look like?

Keep playing with the “book of your business” until you have a much stronger book than when you began.

Consider, then, how you could incorporate these rewrites into real life.

You Have Twenty Books in You

Whether you are planning a book, or are in the midst of writing one, I have some advice that could be a life saver. That is:

Don’t look at this current book as the only one you’ll ever write. If you do, it’ll mess with your head.

How so?

If you’re convinced this is your only book, you’ll stuff it with everything you know – and it’ll grow unwieldy. You’ll try making it perfect – and it’ll end up dull. You’ll want it to be a permanent monument to your very existence – and it’ll turn into an embarrassment.

Trust me, I’ve seen it happen. The harder a writer presses, the more their work suffers.

When I’m coaching a would-be book writer, I put things in perspective. I tell them: “You have twenty books in you. This is merely one of twenty. Treat it that way.”

If the book you’re working on is only a twentieth of your eventual output, that’ll change your approach. Your writing will become focused, your words will flow more easily, and most importantly you’ll be willing to take chances, because your entire life isn’t resting on this one throw of the dice.

Now, you can take my word that you have twenty books in you, or you could give yourself a dose of proof.

Suppose, for instance, you’re a strategy consultant. What books might you write?

You could write a general book on strategy, but you could also write a dozen separate books on strategy’s subcomponents, such as market selection and business unit strategy.

You could write books for different audiences, such as strategy creation for the CEO and strategy creation for a team.

You could write books on capturing different markets, like winning business in newly industrialized countries and winning business with members of Generation Z.

You could write books in different formats, such as a primer, a field guide, a workbook, a 30-day guide to building a strategy, a six-month diary on execution, a 365-day guide of strategy wisdom.

And those are just for starters.

Since we’re looking ahead, you’ll be learning methodologies that don’t exist yet, and you can write about those. You’ll be having experiences you haven’t had yet, and you can write about those.

What’s more, you can write books that are outside the realm of your current business, or that intersect with it indirectly.

If I gave you a couple of hours, your list likely wouldn’t be twenty books long. It would be double or even quadruple that number.

Of course, listing books and completing them are two wildly different matters. Still, taking a stab at this exercise will show that you have a lifetime’s worth of information and expertise to write about — and when you write one book, you build the capacity to write the next.

I have two questions for you, then:

- What are your twenty books?

- Which one will you work on today?

How to Increase Your Work’s Value, Without Much Effort

One morning awhile back, I awoke early and wanted to know the time, so I reached for my iPhone. Inadvertently, I hit the button for Siri, which triggered the message: “What can I help you with?”

Now, up to that point, I had rarely used Siri. Frankly, I’d forgotten she was part of my phone, so out of mild surprise, I didn’t respond. Siri, though, offered encouragement, filling my phone’s screen with sample questions I might ask, such as:

“What’s the NASDAQ today?”

“How’s the weather this week?”

“What are the best pizza stores nearby?”

It was only five in the morning, but that query about pizza stores caught my eye. When I asked it of Siri, she gave me a list of fifteen local pizza shops – several of which were new to me.

This was turning out to be a good day. I hadn’t had my first cup of coffee, but I already knew there’d be pizza for lunch.

From a business standpoint, I thought about what occurred.

Apple knew I’d already owned their product – an iPhone – but they wanted to be sure I knew about all its functionality, so I could get the most out of it.

After all, if there were ways their product could improve my life, but I didn’t know about them or didn’t remember I owned them, it would be a loss for me and for Apple.

For me, the loss would be in personal effectiveness. For Apple, the loss would be in poor word of mouth. (Me: “I heard the iPhone could do so much. I don’t get it. Seems pretty limited.”)

What Apple did, then, was to remind me of functionality I had paid for, but wasn’t using.

The sample questions Siri asked served both as a prompt (Remember, you own Siri) and an enticement (Here are just a few of the cool things Siri can help you with).

More recently, I received a similar reminder about paid-for-yet-unused value from a different source: Amazon.

For years I’ve been an Amazon Prime member, because the service ships books for free. To me, “Prime” equaled “free shipping” — and nothing else.

Then Amazon sent a noteworthy email. In it, the company reminded me that as a Prime member I can also stream thousands of movies at no extra cost. Yet I hadn’t watched a single movie.

I owned a membership, but I wasn’t using that membership to its fullest. Amazon wanted me to claim what was mine. They wanted me to get all I had paid for.

Do you see how important this concept can be for you and your business?

Your clients may adore your work, but they’re likely not wringing as much value from it as they could, because they’ve forgotten (or never knew) all it can do for them.

Your job is to remind them.

Remind clients about the products and services they’ve bought from you, and give them tips on features they may not remember they own, or alternate uses that increase your work’s value in their eyes.

Remember, you’re not trying to upsell them. You’re trying to help them derive greater benefit from what they already own. They’ll love you for that.

I’ll be writing more about this strategy in future posts. But for now, consider ways of making it work for you.

- What would you be reminding clients about?

- What kinds of additional value might they gain?

- How might you do your reminding?

By the way, if you’re a consultant or coach who equips clients with tools, matrixes, and other forms of conceptual heuristics, make sure you remind people about deriving greater value from those, too.

Whatever you try, I’d be excited to hear about it.

The Best Brand Story is Often Informal

Sometimes your best brand story isn’t the one you think it should be. It’s one of your throwaway stories; an informal anecdote everybody else loves, but you don’t think twice about.

I’ll explain.

I recently stopped by a pet food store. Outside sat a brand representative at a table full of a type of cat food I hadn’t seen before.

I asked the rep what made this cat food distinct from the brands inside the shop. She told me an intricate story about single-source proteins. I kind of got the gist, but not fully.

I asked where the food was made. Here’s where things changed. She said, “It’s made in Thailand. Why it’s made there is interesting.” She then told me a story.

One of the brand’s chief investors is a man who travels the world, and wherever he goes he brings along his pets — 25 cats.

One of the brand’s chief investors is a man who travels the world, and wherever he goes he brings along his pets — 25 cats.

During a trip to Thailand, he ran out of the food he customarily feeds his cherished cats, so he tried the local pet food. His cats wouldn’t touch it.

Disgusted, he visited a nearby food manufacturer; one that had no experience with pet food. They had only ever prepared food for human beings.

He told the manufacturer his dilemma, gave them a rough recipe, and offered to pay if they’d make a few dishes for his cats.

Obviously, the manufacturer didn’t know how the dishes would turn out. Still, they agreed to make them. The result?

All 25 cats loved the food. Couldn’t get enough of it. They enjoyed it so much, in fact, that the man contacted an entrepreneurial friend in the United States, and they started selling the Thai-produced cat food here.

I asked the young lady if that story was a formal part of the brand’s sales pitches and marketing materials? She said, no, it wasn’t a story reps were required to use. She had heard it from the head of sales, and thought it quirky and memorable.

I took a few sample cans of the cat food, and thanked her.

When I returned home, my wife asked about the cans. Do you think I talked about single-source proteins? No way. I said:

“Let me tell you the story behind this cat food. There’s this well-to-do man who travels the world, and everywhere he goes he takes along his 25 pet cats. Can you believe that? Anyway, one day he and his cats were in Thailand and . . . “

For us — as consultants and thought leaders — what’s the takeaway here?

In conceiving your brand story, don’t let your thinking become narrow and buttoned up. Make your mind bigger.

Yes, the people in your market need to know your value proposition, but they want to know other things, too. They want to know about you and your philosophy and how you started and what you’ve done and what you plan on doing and what drives you.

Don’t straightjacket yourself by thinking only of terse stories that demonstrate monetary value. Instead, think of all the anecdotes that bring your brand to life. The stand-up-straight professional anecdotes as well as the bed-headed informal ones.

You never know which type will take your market by storm.

(This post was inspired by a comment made by my pal Nick Corcodilos about my previous post. You can read that post and Nick’s comment here.)

How You Tell a Brand Story Matters

Sometimes it’s easier to learn positioning and branding lessons when we look outside our field.

Let’s look at a lesson from the world of fast food. Then we’ll see how it applies to our brands as consultants and thought leaders.

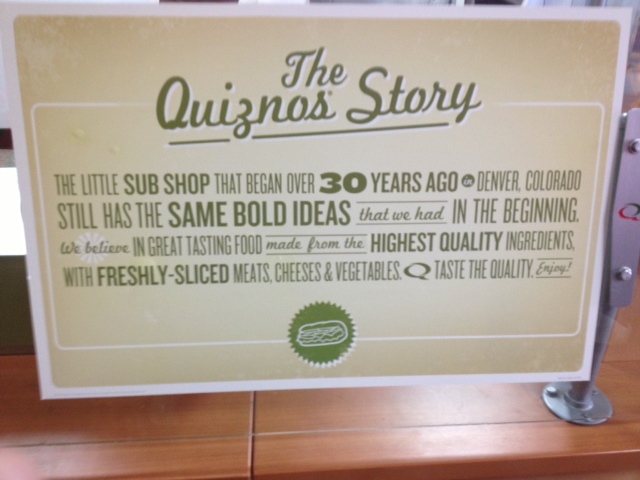

A few days ago, I was eating at my local Quiznos sub shop, and a sign inside the store caught my attention.

The sign is hard to miss. It’s affixed to a barrier separating the food-preparing staff from customers. To place an order, customers more or less have to peer over the sign. Given such prominent placement, it must say something important, right?

Its headline: “The Quiznos Story.”

Now, that headline might not mean much to you, but I’ve got to admit — as a positioning and branding geek — when I first read it my curiosity was piqued. In my world, the word “story” carries weight.

Sometimes story refers to a business’s brand story, and how the business delivers value through a big differentiating idea or striking promise.

Other times story refers to a business’s backstory, which tells us why the business began in the first place, and how what it does is important in ways that go beyond merely making money.

Whatever kind of story being used, when you see the word in a marketing context, you know you’re likely going to find out about the brand’s core idea or competitive advantage.

What’s more, the brand will probably tell its story entertainingly, so you’ll share it with others.

I continued reading.

The sign’s first line taught me three facts about Quiznos: 1. It began, not as a franchise, but as a single store. 2. It started thirty years ago 3. It originated in Denver.

So far, so good. I could picture the company’s birth, because the scene was established with facts. Facts are concrete and fashion explicit images in the mind.

I was ready for the payoff: How is Quiznos different? What intriguing point would I share with my wife and friends? (“Stella, I was in Quiznos today. You want to hear something cool?”)

Here’s where the story sputtered.

The sign’s second line mentioned “BOLD IDEAS,” which threw me. I enjoy Quiznos’ food and atmosphere, but I never think about the experience as bold.

The third and fourth lines explained what Quiznos considered bold: “Great Tasting Food,” “HIGHEST QUALITY INGREDIENTS,” and “FRESHLY-SLICED MEATS, CHEESES & VEGETABLES.”

I felt duped.

Here I was excited to learn what separated a brand I enjoy from the rest of the pack, and what I was fed was a surface story that – excluding the part about thirty years ago in Denver – could have been trumpeted by any competitor.

For a sub shop to say it believes in great-tasting food, consisting of freshly-sliced quality ingredients, is like a automobile manufacturer saying it believes in building cars that drive forwards and backwards. Or, a computer maker bragging about how its machines can connect to the internet.

The story Quiznos told may be true, but it wasn’t told in a way that would make a dent in anyone’s consciousness. I’m guessing few customers have read that sign fully or remember what it said if they did.

What can we as consultants and thought leaders learn here?

How we tell a marketing story matters. If we tell people only what they know and expect, they’ll ignore us.

What our brand story or backstory needs is . . . a context . . . an insight . . . a promise . . . a substantiation . . . a frank detail . . . an unexpected bit of color . . . that forces our audience to look anew at what they thought they already knew.

For example, if you’re a consultant whose main message is about helping organizations “change” and “accelerate results,” you’re not giving your audience any reason to consider you over a competitor, because you sound like hundreds of thousands of other consultants.

Your language is too general. There’s nothing for us to picture. Your message needs a meaningful difference and specifics.

You need to tell us things you know, but we don’t. Doing so will make us sit up and take notice. We may also be intrigued enough to call you so we can find out more.

If you’d like to try your hand at creating a brand story that people will remember, consider the following three questions:

1. What do you know that (most of) your market doesn’t know about your subject?

2. What do you know that (most of) your market doesn’t know about your company?

3. In answering the first two questions, what ideas and stories did you discover that your market would find equally surprising and valuable?

Your answers can serve as the basis for a draft of a brand story that is fresh, exciting, and uniquely yours.

Writing an Elevator Speech “Lifelike in the Extreme”

To prepare for a workshop I’m giving, I’ve spent hours doing exploratory writing on how to create an elevator speech.

On the page, I’ve asked and answered questions like, “What’s an elevator speech supposed to accomplish?,” “What are the best ones I’ve heard?,” and “What are the worst ones?”

I’ve also made a list of elevator speech ingredients. Most of them, naturally, are the things you’d expect. A good speech mentions one’s target market, product or service, and benefits to the customer.

One of the ingredients I came up with, though, is more unusual. You rarely hear about it in business literature. That often overlooked ingredient is honest detail.

To better describe what I mean by honest detail, which might also be called “telling detail,” let’s turn to an outside source: novelist and essayist, George Orwell.

A Detail Saves a Life

In late 1936 to early 1937, Orwell fought in the Spanish Civil War. During one battle he was shot in the throat. Orwell not only recovered, but in the ensuing twelve years he penned his most notable books, “Animal Farm” and “Nineteen Eighty-Four.”

He also wrote an essay, “Looking Back on the Spanish Civil War,” which included the following passage:

“At this moment a man, presumably carrying a message to an officer, jumped out of the trench and ran along the top of the parapet in full view. He was half-dressed and was holding up his trousers with both hands as he ran. I refrained from shooting at him . . . I did not shoot partly because of that detail about his trousers. I had come here to shoot at ‘Fascists’; but a man who is holding up his pants isn’t a ‘Fascist,’ he is visibly a fellow-creature, similar to yourself, and you don’t like shooting at him.”

“At this moment a man, presumably carrying a message to an officer, jumped out of the trench and ran along the top of the parapet in full view. He was half-dressed and was holding up his trousers with both hands as he ran. I refrained from shooting at him . . . I did not shoot partly because of that detail about his trousers. I had come here to shoot at ‘Fascists’; but a man who is holding up his pants isn’t a ‘Fascist,’ he is visibly a fellow-creature, similar to yourself, and you don’t like shooting at him.”

In analyzing this passage in their textbook, “Finding Common Ground,” educators Carolyn Collette and Richard Johnson write: “The life of Orwell’s enemy may have been spared because Orwell noticed a detail, the man holding his pants up with both hands – an awkward, slightly comical, and bizarre detail; lifelike in the extreme . . . “ (p. 4)

The honest detail, “lifelike in the extreme,” can persuade. The telling image – drawn, not from the mind, but from reality — can capture people’s attention and coax them into action.

Most business writing, especially elevator-speech writing, lacks such realism and candor. It stays on the surface, espousing “big ideas” through generalization and abstraction. The writer ends up saying what they think they’re supposed to say, instead of what’s real. Their words don’t make a dent in anybody’s mind.

Statistics as Detail

When I started Levy Innovation, my elevator speech used to talk about how I helped make people memorable and compelling. As I’ve written before, there was nothing wrong with saying those things. I still say them. What I hated was talking about those concepts in unsubstantiated form. Without supporting facts and detail drawn from life, they were mere opinion.

As I examined my projects for facts, I realized something that had previously escaped me. Due in part of my efforts, several clients had become popular enough to raise their fees by 600%, 800%, and even 2,000%.

Figures like those became my substantiation — my telling detail. When asked what I did, I began saying: “Consultants and entrepreneurial companies hire me to help them increase their fees by up to 2,000%.”

Painting a Candid Picture

While creating elevator speeches for other situations, I always sought that telling detail to make my point. Sometimes the detail came in the form of a statistic. Other times it came by painting a picture that let the listener know I understood what they might be going through.

For instance, if I met a consultant who explained their services awkwardly or seemed embarrassed as they spoke, I’d introduce my work in the following way:

“You know how when a businessperson meets a prospect, say, at a conference, and that businessperson starts talking about who they are and what they do, and the prospect starts looking right past them to see if there’s anyone in the room who is ‘more important’?

“So, not only has that businessperson lost any chance to gain a client, but they also feel awful about their life, because they put so much effort into their business, and this prospect looking past them is, in a way, dismissing their entire being. (At least that’s what it feels like to them.)

“Well, what my work does is to help people like that businessperson who find it tough explaining what they do and why their work matters. I counsel them on writing elevator speeches and talking points that hold attention and make prospects eager to have a conversation with them.”

More times than not, the person I was talking to wanted to find out more about how my work might help them, because the details of the picture I painted struck them as undeniably real.

(Where, you might wonder, did I get those details? From my own life. A couple of decades ago, while I was in my early twenties and manned the trade show booth for a book wholesaler, attendees would ask me, “What does your company do?” As I explained, they’d at times leave while I was in mid-sentence. You don’t forget a detail like that.)

“Help me! Help me!”

The other day I spoke with a consultant, Kathy Gonzales, whose elevator speech delighted me. It’s not because Kathy meticulously crafted every word, or delivered the speech with flair. It was the realism of her detail. Her speech sounded like it came straight from life. When I asked what she did, she said:

“I work with executives, mostly men, who want to leave the corporate world and start their own business. I don’t make them better at what they want to do. I won’t make a financial planner a better financial planner, or a baker a better baker. I just help them make the jump. They’ve got one hand on the corporate ledge, and they want to let go, but they’re crying, ‘Help me! Help me!’ That’s my client.”

Notice how Kathy didn’t make a lot of promises or claims. That adds to the persuasiveness of her speech.

I don’t know anything about Kathy’s company, Modern Happiness, and I’m not in the market for her type of service. But if I was, I’d be intrigued enough to have an initial chat – a “How do you do that?” talk — and that’s what an elevator speech is supposed to accomplish, isn’t it?

Your Challenge

If you’re struggling to come up with an elevator speech that captures attention, here’s an assignment using a standard speech format:

Think about the three most common problems your product or service solves, and create a speech for each. Don’t labor over the speeches, though. Just talk them out. Consider recording them as you go.

As I did in a speech above, begin with the phrase, “You know how when . . . ,” and describe the type of person you serve and the problem they experience in as much honest detail as you can. Stay true to what really happens. Don’t think you need to make things sound more dramatic than they are.

Once you’ve painted the scene, talk about what your work does to alleviate the problem you mentioned.

You may not get the most telling details right away — the ones, “lifelike in the extreme.” If not, don’t sweat it. As you do your project work throughout the day, pay attention to what really happens and try incorporating the most intriguing facts into future drafts of your speeches.

Business Guidance from the Future

I asked my friend, Jake Jacobs, how business was doing, and expected a mechanical response, like “Things are good” or “Can’t complain.”

I asked my friend, Jake Jacobs, how business was doing, and expected a mechanical response, like “Things are good” or “Can’t complain.”

Instead, he told me he’s having the most profitable twelve months he’s had in twenty-five years as a consultant – and that’s in a down economy. This year, in fact, his firm is exceeding last year’s revenue by 170%.

How’d that happen?

A few months back, Jake did a little soul searching, and decided he wanted his company, Winds of Change Group, to hit the five-million-dollars-a-year revenue mark. Reaching that figure, though, would represent a jump. A jump that would take considerable time.

Jake, however, didn’t want to wait.

He knew if his company was to have any kind of shot of reaching that goal sooner rather than later, they couldn’t continue doing things the way they’d been doing them. To find out exactly how they should change, Jake took an unusual approach:

He projected himself into the future, and found his answers there.

That is, he didn’t first look at how his company could inch-ahead with what they were currently doing. Instead, he conducted a thought experiment, and imagined himself in the near-future heading a consultancy that was doing five million dollars business a year already.

A Vivid Daydream

During the experiment, which was something of a vivid daydream, Jake looked at each part of his firm and noted how they were conducting business. He saw who they had as clients, what services they were offering, how they closed deals, and how they delivered upon promises.

After conducting the thought experiment, Jake shared what he saw with his colleagues. Together they began taking immediate action on as many of his future-focused tactics as they could – thus behaving as if they were a five million dollar firm in the here and now.

They haven’t yet hit their revenue goal, but with increases of 170%, hitting that figure shouldn’t take long.

What tips can Jake share about his living-in-the future approach?

- “When you’re looking around in the future, don’t just see the big stuff, like who your clients will be. You’ve got to study every nook and cranny of your organization. So, if you’re looking at your future company, see how it would celebrate its successes. What would its parties look like?”

- “As much as possible, make that preferred future real today. Doing the stuff you’ve brought back is energizing. You start seeing results and evidence of change immediately. The more things change, the more your people see that they’re changing, the more likely they are to push for more change. It’s self-reinforcing.”

- “You can use this method in any aspect of your life. Why not have an image of the next hour being the way you want it to be. Give it a try, and check in sixty minutes later to see how it works.”

Your Assignment

Try Jake’s preferred future exercise during your next bout of freewriting.

First, do a twenty minute session on what your dearest business goals might be, and what your company would look like once you’ve reached them.

Second, do another twenty minute session on what you learned during the first session, and what you could apply to your business today if you chose to.

Writing a Sticky Title

Let’s begin with a quiz. Below you’ll find a list of book titles. All are genuine titles from published books – except for one. See if you can spot that lone non-book-title.

1. “Theodore Roosevelt on Leadership”

2. “Curious George and the Pizza”

3. “Soon I Will be Invincible”

4. “The Confident Leader”

5. “Virtual Learning”

6. “Sixty Stories”

7. “Apathy”

8. “The internet isn’t that big a deal. Neither is the PC. Abandon all technology and live in the woods for a week and see if it’s your laptop you miss most. In fact, the technologies most important to us are the older ones – the car and telephone, electricity and concrete, textiles and agriculture, to name just a few. The popular perception of modern technology is out of step with reality. We overestimate the importance of new and exciting inventions, and we underestimate those we’ve grown up with.”

Think you know the answer? We’ll get back to the quiz in a moment, and see if you’re right.

Two Methods of Titling a Book

As a book-writing coach for businesspeople, I’m often asked about how to come up with a sticky title. I have a bag of titling tricks, but here are two of my favorites:

Sticky Trick 1. If the writer has written a book draft or proposal, I ask that they print it out, and underline all the interesting ideas and turns-of-phrase they see. We then comb through their work and make up dozens of titles based on every promising phrase they’ve highlighted.

Sticky Trick 1. If the writer has written a book draft or proposal, I ask that they print it out, and underline all the interesting ideas and turns-of-phrase they see. We then comb through their work and make up dozens of titles based on every promising phrase they’ve highlighted.

The advantage of this approach: The titles we create are based on the writer’s organic material. That is, rather than focusing everything on the book’s generic idea (for instance, how to be more productive), we can look for how the writer makes their point in distinctive ways (how to be more productive by being “unreasonable”).

Distinct ideas and phrases are what’s going to make the book stand out in the marketplace when it’s published, so why not start titling it from there?

Sticky Trick 2. The writer and I visit bricks-and-mortar and online bookshops, and we see which book titles catch our attention. Those attention-grabbers act as thought starters, and inspire us to come up with fresh titles.

This method harkens back to the quiz I asked you to take. You looked at eight choices and picked the one that wasn’t a published book title. The answer, of course, is choice 8 (“The internet isn’t that big a deal . . . ,“ which is from Bob Seidensticker’s excellent book, “Futurehype: The Myths of Technology Change”).

I’m certain you selected the correct answer, but how did you know it was correct?

Obviously, book titles follow certain rules of thumb. Perhaps you’ve never articulated these rules, but you know many of them inherently. They’re a part of you.

You know, for instance, that a title must be short. While choice 8 was a powerful piece of prose and encapsulated the main idea of Bob’s book, it violated the brevity titling rule. Therefore, it couldn’t have been the title. (A number of books have had lengthy titles for novelty’s sake. The longest title on record, which celebrates the career of “Harry Potter” actor Daniel Radcliffe, is 4,805 characters.)

What are some other rules for titling a book? Again, an easy way of reminding yourself of rules you already know, or of finding new ones, is by studying existing books and extracting the concepts they use.

Look, for example, at my book, “Accidental Genius.” The title was inspired by a quote from Samuel Johnson. One rule, then, might be, “Title your book using a full or condensed quote.” A second rule could be, “Put together two conflicting words (like ‘Accidental’ and ‘Genius’) that intriguingly point to your book’s main premise.”

Tweetable Titles

Roger C. Parker, a smart and prolific writer who has penned 38 books, has collected dozens of titling rules, and has published them in a book called “#Book Title Tweet.”

The work’s central premise: for a title to be effective, it’s got to be able to “communicate at a glance.” The discipline of training yourself to write Twitter-friendly titles, then, is a useful one. Roger’s book, in fact, dispenses its wisdom in approximately 140 tweet-sized chunks, including:

- “[P]osition your topic by making it obvious whom you are not writing for, e.g., ‘Design for Non-Designers.’”

- “Target your title to a specific circumstance, e.g., ‘How to Sell When Nobody’s Buying.”

- “Position your book by projecting an ‘attitude,’ – ‘Mad Scam: Kick-Ass Advertising Without the Madison Avenue Price Tag.”

- “Issue an engaging command and explain it, e.g., ‘Don’t Make Me Think: A Common Sense Approach to Web Usability.”

- “Ask a question while stressing your unique qualifications, e.g., ‘What Can a Dentist Teach You about Business, Life, & Success?’”

Besides titling tactics, Roger shares bite-sized research and survey tips, and cautions.

At 130-odd pages, “#Book Title Tweet” is a speedy read, the information in it is first-rate, and the importance of its concept is undeniable.

After all, without a strong title, it doesn’t matter how good your content is — no one will read your book, white paper, or article, click on your video, or attend your event.

You owe it to yourself and your work, then, to devise titles that stick in the mind or prompt a click.