Besides being a business consultant, I’m also a magician. I invent illusions, design magic shows, write instructional magic books, and position performers.

Besides being a business consultant, I’m also a magician. I invent illusions, design magic shows, write instructional magic books, and position performers.

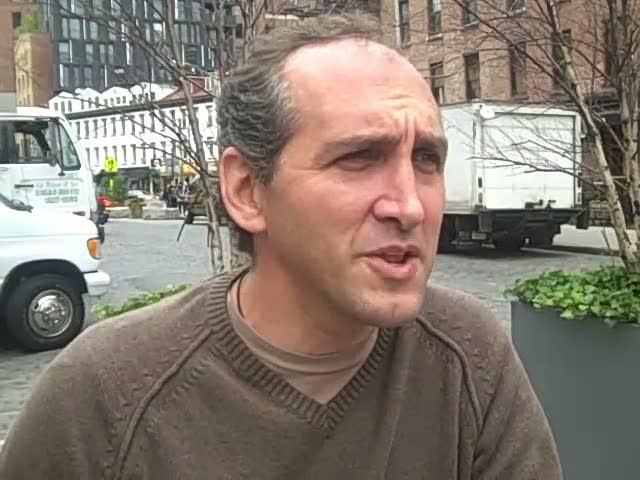

If you read Seth Godin’s recent post about Steve Cohen, “The Millionaires’ Magician,” you’ve seen my work in action. Steve has been my client and friend for a decade. I positioned him, and co-created his two Off-Broadway shows, “Chamber Magic” and “Miracles at Midnight.”

Steve and I have invented several tricks I think of as theatrical. I’d like to tell you about one.

Years ago, when “Chamber Magic” was getting off the ground, Steve gave me a call. He said a New York newspaper reporter had been in the audience, was impressed, and asked to meet Steve later in the week for an interview. If the interview went well, the newspaper would devote nearly a page to the story. Steve and I took this as a challenge. An article in a New York paper was worth thousands of dollars of publicity.

During a fast brainstorm, I hit upon an idea. We drafted an email and shot it off to the reporter. The body of the message read something like this:

“Steve Cohen here. Thank you for offering to interview me. Let’s meet tomorrow in Manhattan at noon at the National Arts Club. And, if you’re game, I’d like you to participate in an experiment.

“On your way here, keep a running tally of every red car you see.

“Don’t, however, write down or mention the final figure to anyone. It should remain a secret until we meet. Just keep it fixed in your mind.

“A few additional points:

“You told me you live in Brooklyn, which is six miles from where we’ll be meeting. You have a few routes you can travel. Perhaps you’ll take the Brooklyn Bridge. Or, the Manhattan Bridge. Or, the Williamsburg Bridge. You also have the choice of dozens of avenues and streets.

“What’s more, you have several transportation methods you can use. You can walk, cycle, rollerblade, drive, grab a cab, board a bus, ride a horse, take a helicopter, or mix and match. Each method will likely alter your route some. That’s fine. It’s your choice.

“Then, there are the cars. You decide what constitutes a ‘red car.’ It can be completely red or have just a red detail. It can be moving or parked. You can count red trucks and SUVs, too, or you can ignore them. Follow your impulse.

“Again, make sure you’re not making your counting obvious. No fingers or pads of paper. And, take precautions that you’re not being followed (check the foot traffic, the autos, and the air).

“See you tomorrow.”

The next day, Steve was waiting as the grinning reporter walked in and said: “I couldn’t sleep last night. I have a feeling you’re going to tell me how many red cars I’m thinking of.”

“Did anyone follow you?” asked Steve.

“No,” said the reporter.

“Did you see red cars?”

“I did.”

“Did you write down how many you saw, or share that figure with anyone?”

“No.”

“But you have the number safely in mind.”

“I’m thinking of the number, yes.”

“You’re not going to change it, will you? I mean, you’re a reporter and are sworn to the facts and the truth.”

“I promise I won’t change it.”

Steve picked up a business card, scribbled a figure on it with a pencil, and held the facedown card out to the reporter.

“How many red cars did you see?” asked Steve.

“61.”

When the reporter turned the card over and saw a penciled “61,” he punched and kicked the air, shouting, “Man! This almost makes me believe in real magic!”

Steve got his article.

Why did I tell this story? I told it because, well, it’s a damn good story. Its got an intriguing premise and action that unfolds on the streets of Brooklyn and New York. It’s also got a big city reporter who’s so affected by the experience that he lies awake in anticipation and nearly starts believing in miracles. What could be better?

Stories are what remains long after the show has been packed away. They’re evidence that miracles occurred.

When Steve and I come up with an illusion for him, we simplify it until we believe it’s easy for audiences to remember and talk about. If they do talk about it, great. If they don’t, we pull it from the show and start over. Everything we invent is based on the memories it provokes.

Doing tricks that lead to stories is forceful marketing. The audience acts as missionaries and carries word of the show with them.

If you dare to take the same approach in your business, you may see miracles happen there as well. Once you’ve completed a project and are heading home, ask yourself “What will remain? What will clients talk about? What will they be excited by? What won’t they be able to forget? What will they share?”

(This post is drawn from an article I wrote for “Genii,” a venerated magic magazine published by Richard Kaufman.)