Freeing Yourself From Gurus

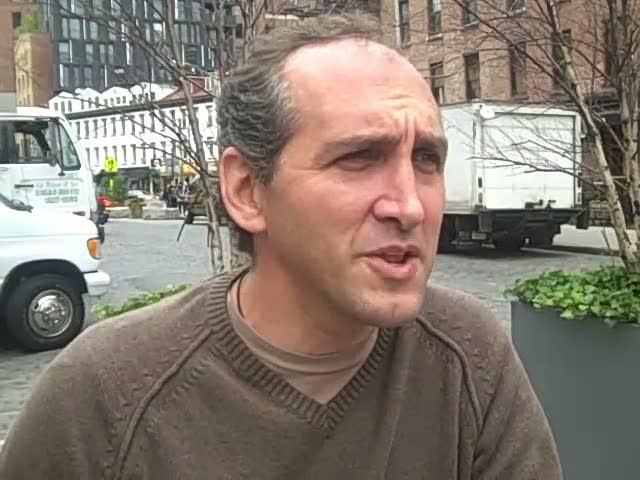

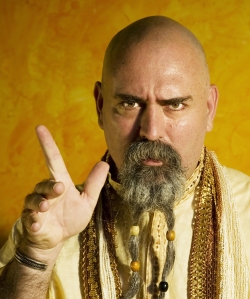

A consultant named Tim was telling me about the field he worked in. He, in fact, wanted to write a book about it. Tim admitted, though, that he was intimidated by a famed guru who has spent years speaking and writing in that same field as he.

What, Tim wondered, could he possibly say that hadn’t already been said by the guru?

What, Tim wondered, could he possibly say that hadn’t already been said by the guru?

I’ve heard that lament before. What it comes down to is this:

Tim was confusing the guru’s contribution to the field with the totality of that field. He was looking at the guru’s opinions, excellent though they might be, as the only ones possible. It was as if the guru’s smarts, charisma, and accomplishments were blinding him to all the alternate ways of approaching the subject.

“Let the work of this guru inspire you.” I said. “Be grateful that such a vivid thinker has shared so much. Celebrate him and parade his work to others. But don’t let the strength of his voice stop you from using your voice.”

Each of us has something distinctive and interesting to contribute if we give ourselves the freedom to do so. We have experiences, stories, and ideas that can add texture to a subject, or take it in new directions.

At times, though, we must free ourselves from the magnetic pull that we’ve let others have on our thinking.

One way of giving yourself distance is by studying the subject you want to write about more comprehensively. You may, in fact, be unduly influenced by a guru’s work, because you’re focused too narrowly on their thinking to the exclusion of others.

Another way of giving yourself distance is by examining your career, not at first for abstract ideas, but for concrete success stories. Once you’ve jotted down a few stories, study them and see if any insights appear organically. You may be sitting on an unusual approach or helpful anecdote, and you don’t even realize it. Let the facts lead you.

Remember, each of us can contribute. We have knowledge and perspective that could help others if only they knew about it. Don’t let others’ outstanding work blind you to the value of your own gifts and experiences.